Blue-green algae blooms, once unheard of in Lake Superior, are a sign that ‘things are changing’ experts say

Aug 15, 2022 10:21AM ● By Content EditorBy Caitlin Looby - Milwaukee Journal Sentinel - August 12, 2022

Brenda Moraska Lafrancois was on her way back to her office when she first heard reports of algae blooms near the sea caves along the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore on Lake Superior.

It was a calm, hot day in August 2018 — just the right conditions you expect for a bloom. Just not the lake you expect.

When she got to Meyers Beach an hour later, the bloom had already dissipated. In the 10 days that followed, opaque green water cropped up in waters stretching over 60 miles from Superior to the eastern Apostle Islands.

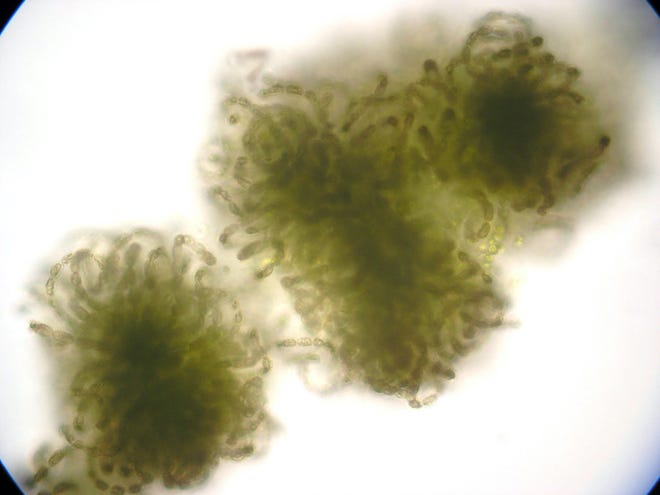

Warm water, sunlight and nutrients can cause blue-green algae to reproduce quickly, or bloom, causing clear water to turn into thick, green scum.

The first blue-green algae bloom appeared in Lake Superior a decade ago and until 2018, the blooms were small and short-lived, lasting from only a few hours to a day.

But for Lafrancois, an aquatic ecologist for the National Park Service, a “sinking feeling” lingered long after the 2018 bloom. She realized this “wasn’t just a fluke but maybe part of a recurring pattern.”

Algae blooms emerge every summer in Lake Erie, Lake Michigan’s Green Bay and Lake Huron’s Saginaw Bay, largely a result of an overabundance of nutrients from fertilizer, wastewater and stormwater runoff.

But Lake Superior is the northernmost and by far the coldest of the Great Lakes, with typical summer surface temperatures around 60 degrees compared with 75 degrees for Lake Erie. What's more, its shoreline is not as developed as the others, nor is there a heavy agricultural presence nearby.

Nevertheless, blooms have been reported in the lake every year since 2018, leaving scientists questioning why this is happening and what it means for the lake. The likely cause: warming waters and intensifying storms from climate change.

“Lake Superior may be sending us some signals,” said Kait Reinl, a scientist who studies what causes blue-green algae to bloom in Lake Superior.

In the other Great Lakes, the blooms are so thick, the algae can suck up all the oxygen, creating a dead zone below when they die off. They can also release microcystin, a nerve toxin that threatens humans and pets.

Up until last year, the Lake Superior blooms didn’t produce toxins — at least not ones that are harmful to humans. Experts say it's unclear whether the blooms will one day release microcystin in the deep, open water, but the shorelines and waterways close to the lake are a different story.

According to Reinl, last summer scientists found traces of the toxin at Barker’s Island Beach near Superior that were just above the Environmental Protection Agency's recommended limit for swimming and other recreation activities.

Marvin Defoe, the tribal historic preservation officer for the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, is concerned that algae blooms cropping up in the inland waterways may jeopardize the tribe's treaty rights to hunt, fish and gather off-reservation. Defoe fears that the blooms may change the behavior of wildlife or force fish out into colder, cleaner, deeper water, making it harder for tribal members to harvest resources.

He also wondered whether these blooms would threaten manoomin, or wild rice, a sacred food for the Ojibwe people, grown in coastal wetlands and inland lakes along Lake Superior. Manoomin is already threatened by habitat loss, water quality, human activity and disease outbreak.

“I hope that it doesn’t become more prevalent because it’s (going to) have an impact on our ecosystem and the other elements of nature,” he said.

Are these blooms new or are we just paying attention?

While these blooms are commonly referred to as blue-green algae, they aren’t technically algae, they are a kind of bacteria called cyanobacteria.

A team of scientists is digging into the sediment at the bottom of the lake and using DNA tools to see how deep they can find the cyanobacteria. The deeper they find the cyanobacteria, the older they are.

“We can go back in time,” said Cody Sheik, a microbiologist at the University of Minnesota, Duluth. “As we go deeper and deeper and deeper into the mud, (each layer of sediment) gives us a slice of history.”

So far, his team has observed the DNA from these cyanobacteria deep within the sediment, telling them that they've been around for a long time and perhaps as long as several hundred years, said Sheik. But it doesn’t appear that these cyanobacteria formed blooms prior to 2012. Or at least there are no confirmed records. One study from 1968 referred to “green illusion water” occurring in late summer on Lake Superior.

After the 2018 bloom, the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission looked into what traditional ecological knowledge was available about these blooms.

The commission represents eleven Ojibwe member tribes in Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan to ensure their treaty rights are upheld.

So far, it appears as if there is no historical knowledge of blooms occurring. Defoe also believes these blooms are new and has yet to hear any stories that include them.

“It’s an indicator that things are changing around the lake,” he said.

A sentinel of climate change

Lake Superior is an important natural resource, holding 10% of all the world’s freshwater. But it’s the second-fastest warming lake in the world behind Sweden’s Lake Fracksjön, warming well above the global average.

And along with Lake Michigan, it may be ice-free by the end of century if greenhouse gases are not mitigated.

Losing ice early gives the water more time to warm, leading to year-round impacts on the lake ecosystem and opening it up to algae blooms.

The typical recipe for a bloom also includes lots of nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus, largely from agricultural practices.

But farms don’t neighbor Lake Superior the way they do Lake Erie and Green Bay — the poster children for algae blooms. And according to Bob Sterner, the director of the Large Lakes Observatory in Duluth, Minnesota, there is no reason to believe that nutrients are loading up the lake. In fact, Duluth Harbor is a lot cleaner than it used to be.

“The one thing we can really strongly point to so far is climate,” Sterner said.

Both major blooms in 2012 and 2018 happened right after 500-year rainfall events, so Sterner suspects the heavy rainfall injected the lake with enough nutrients to incite a bloom.

Lake Superior blooms also only happen in warm years, says Sterner, noting the difference between a warm and cold year is only about 5 degrees. That difference may not be noticeable to beachgoers, but it is to bacteria.

But how and why some blooms produce toxins is still a bit of a mystery — something Reinl is working on.

Even though experts are skeptical that toxins will be formed and released in deeper water, Reinl is concerned that they are seeing them in the parts of the lake that people are interacting with, like shorelines and tributaries.

‘It’s an opportunity,’ scientists say

Since the 2018 bloom, Lafrancois from the National Park Service says that monitoring has ramped up and the Park Service has worked with the Wisconsin Department of Health Services to create signs to better educate the public on what to look for and how to report it.

So far, this year is still a question mark. There have been no reported blooms. But summer had a late start in Lake Superior, with the water experiencing almost record low temperatures for the end of July.

And although Lake Superior’s future is a little less clear, Reinl said that “it’s not all bad news," hoping scientists can find answers before the blooms get worse.

"It's an opportunity to be proactive instead of reactive,” Reinl said, noting there is now a large, coordinated effort to uncover some of these mysteries.

Not only are scientists looking back in time into the lake sediment, they also recently got funding to compare the algae in Lake Superior with the other Great Lakes to see what similarities and differences exist.

Since scientists can't be everywhere, and the blooms can be short-lived, they count on reports from swimmers and boaters. The more complete the information scientists have, the better they can understand the blooms.

Reinl thinks the blooms are just the beginning of something that could potentially become bigger and more regular.

“I am certainly concerned, mostly about the future and whether … we’re on the cusp of something more significant,” he said.

“Only time will tell.”

To read this original story and more news, follow this link to Milwaukee Journal Sentinel website.